From EVs and batteries to autonomous vehicles and urban transport, we cover what actually matters. Delivered to your inbox weekly.

For years, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles were billed as the next big thing, a zero-emission breakthrough that could outdrive EVs and refuel in minutes. Automakers like Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai bet big on the tech. Governments backed it. Headlines called it the future.

But then… nothing.

Today, hydrogen-powered cars make up less than 0.1% of global vehicle sales. Public refueling stations are rare. And most major automakers have quietly pivoted to batteries instead.

So what went wrong?

Was hydrogen always the wrong tool for the job, or did EVs just win faster?

For a moment, hydrogen looked unstoppable.

Automakers poured in billions…

Global hydrogen vehicle sales fell 36% year-over-year in Q1 2024, totaling just 2,382 units, compared to over 3 million battery EVs sold in the same period

Hydrogen cars didn’t fail because they weren’t clean or technically sound. They failed because they were too complex, too expensive, and too disconnected from how real people move.

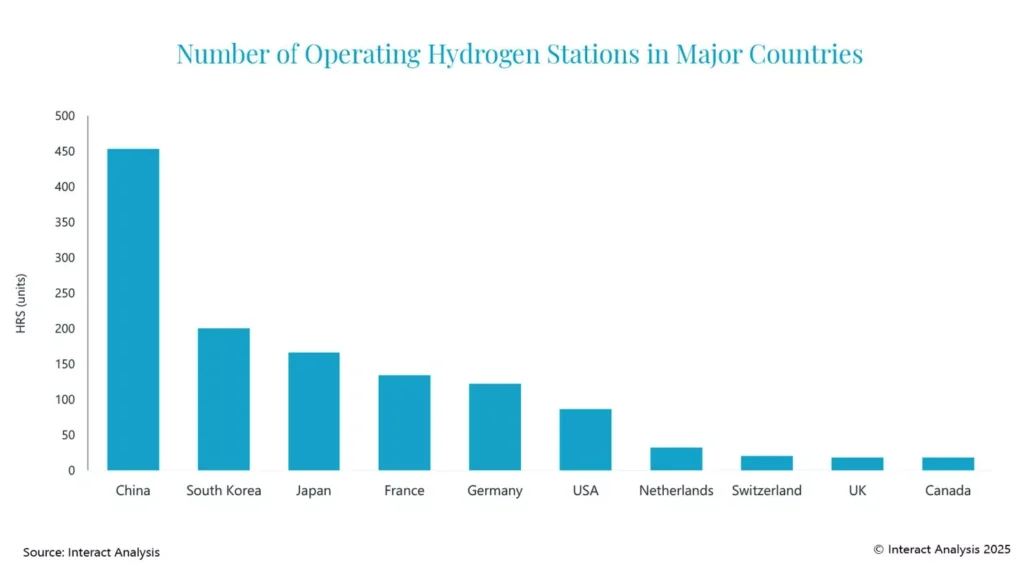

As of the end of 2024, there were approximately 1,160 hydrogen refueling stations worldwide, with nearly 80% located in just five countries. In the United States, there were 86 hydrogen stations, with 73 situated in California alone . In contrast, there were over 4 million public EV chargers globally in 2023 . This disparity makes hydrogen fueling options scarce and inconvenient for most consumers.

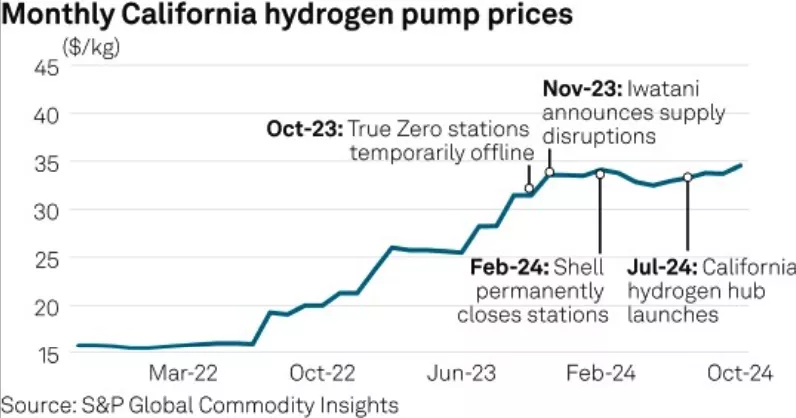

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) are generally more expensive than battery electric vehicles (BEVs). The initial cost of an FCEV can be as much as twice that of a BEV . Additionally, the cost of hydrogen fuel is significantly higher. For instance, in California, hydrogen fuel prices have reached up to $36 per kilogram, making it almost 14 times more expensive to drive a Toyota Mirai compared to a comparable Tesa EV.

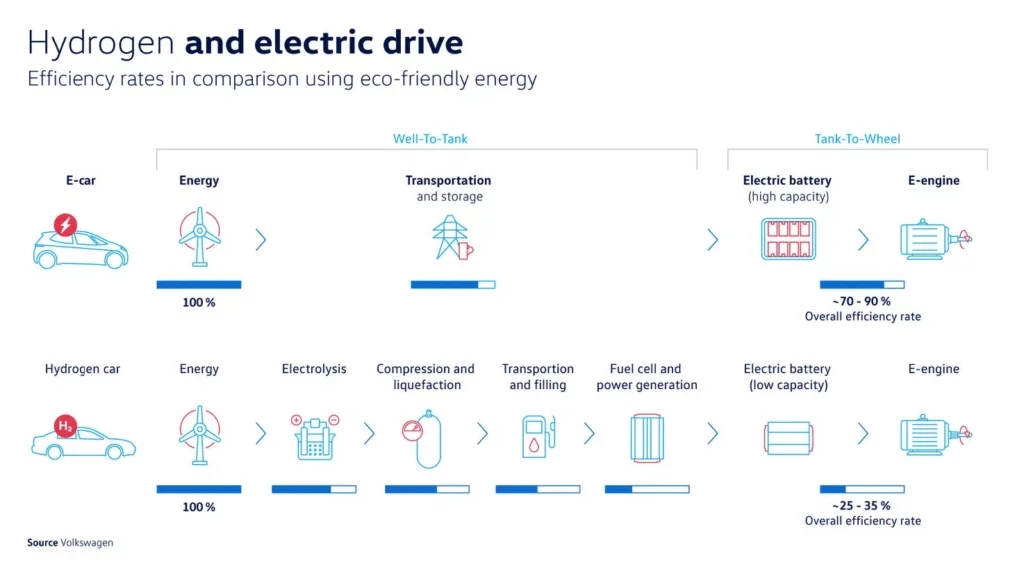

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are less energy-efficient than battery electric vehicles. The overall well-to-wheel efficiency of hydrogen vehicles is approximately 25–35%, meaning they require 2–3 times more energy to drive the same distance as a battery electric vehicle, which has an efficiency of about 70–90% .

Unlike BEVs, which can be charged at home, work, or public charging stations, hydrogen vehicles require specialized fueling stations that are expensive to build and maintain. The capital cost of a hydrogen fueling station can range from $2 million to $5 million, depending on capacity and technology. This high infrastructure cost limits the scalability and convenience of hydrogen fueling networks.

Hydrogen didn’t just lose. BEVs exploded like very few imagined…

Nearly 1 in 4 cars sold globally is electric today. While fuel cell vehicles struggled to leave California, battery EVs went global. Why exactly?

First, the charging infrastructure exploded: by 2023, there were over 4 million public EV chargers worldwide, and unlike hydrogen, BEVs could also be charged at home, at work, or at shopping centers no need for multi-million-dollar refueling stations.

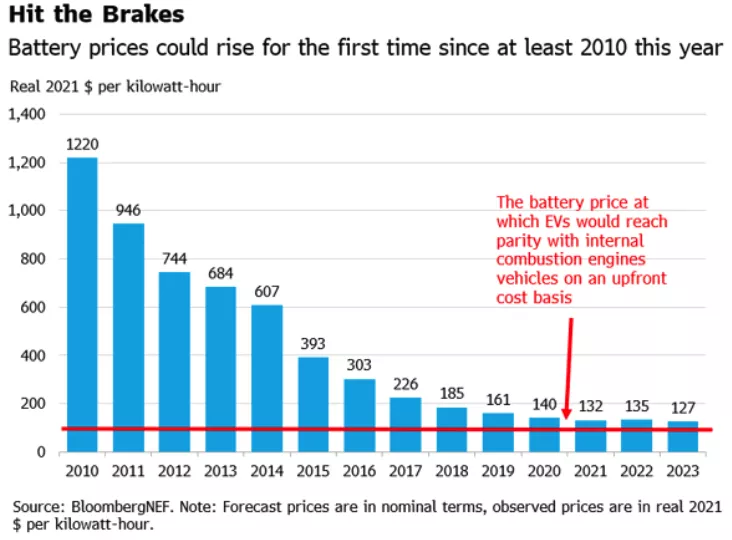

Second, battery costs dropped by more than 80% since 2013, making EVs cheaper to produce and more attractive to buyers, especially when paired with government incentives like tax credits. In contrast, hydrogen vehicle costs remained stubbornly high, and hydrogen itself often sells for more than $36 per kilogram, pricing it far above electricity on a per-mile basis.

Finally, BEVs benefit from simpler supply chains: they rely on electricity and lithium, both already integrated into the global energy system, while hydrogen requires energy-intensive production, high-pressure storage, and an entirely separate distribution network. In short, battery electric vehicles were faster to scale, easier to fuel, and cheaper to own, and that’s why they pulled away.

Hydrogen didn’t win the passenger car race, but that doesn’t mean it’s useless.

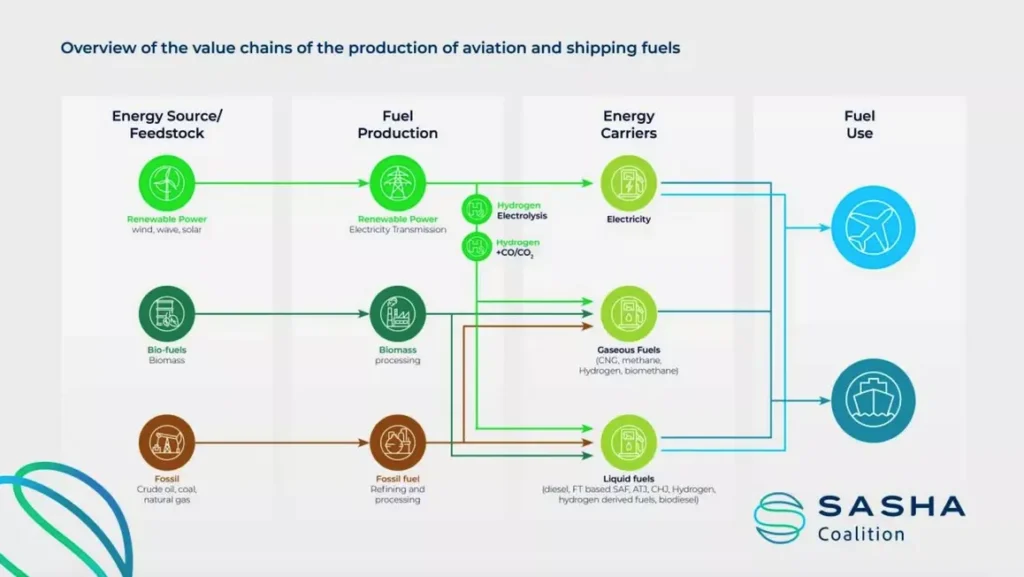

In fact, hydrogen may still have a key role to play in sectors where batteries struggle: heavy-duty transport, long-haul logistics, aviation, and hard-to-decarbonize industries like steel, cement, and chemicals.

Battery weight and recharge time become serious constraints for heavy-duty freight. That’s where hydrogen shines, offering fast refueling and long range without eating up cargo space. Companies like Nikola and Hyundai are actively piloting hydrogen trucks in the U.S., Europe, and South Korea.

Maritime freight and aviation require high energy density fuels, and hydrogen (or hydrogen-based fuels like ammonia or synthetic kerosene) could offer a cleaner alternative to bunker fuel and jet fuel, especially as the EU and IMO push decarbonization mandates on international shipping.

Beyond mobility, hydrogen is increasingly seen as a tool for industrial decarbonization, replacing natural gas in steel production or acting as long-term energy storage for wind and solar. This is where green hydrogen (produced from renewables via electrolysis) may finally earn its stripes, just not behind the wheel of your car.

Maybe. But it’s a long road.

Even with sales stuck in the slow lane, some automakers haven’t given up on hydrogen-powered passenger vehicles. BMW is one of the few European OEMs still investing in the tech, recently announcing its plan to bring a small fleet of hydrogen-powered iX5s to market as part of its broader fuel-cell research strategy.

Meanwhile, Hyundai is doubling down, unveiling a redesigned Hyundai Nexo with upgraded fuel-cell stacks, better range, and sleek new styling. The company continues to frame hydrogen as a long-term play one that could complement its EV lineup, not replace it.

These efforts are more about winning today’s market, hoping for a future where green hydrogen gets cheaper, charging infrastructure hits limits, or fuel cell tech finally crosses the affordability threshold.

But let’s be clear: hydrogen cars are no longer the front-runners. They’re the wildcards still in the game, but running far behind.

💬 What do you think?

Could hydrogen cars still make a comeback, or is this a tech that missed its moment?

Drop your thoughts below 👇 And subscribe for more sharp takes on the future of mobility.