From EVs and batteries to autonomous vehicles and urban transport, we cover what actually matters. Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Cities grabbed the headlines. Suburbs hold the real challenge.

Micromobility crushed downtown traffic. EVs packed urban garages. But what happens when you’re 15 miles out, no bus stop in sight, and sidewalks are just decorative?

Suburbia wasn’t built for flexibility — it was built for cars. Endless driveways, zoning laws from the 1960s, and a mobility system that assumes everyone owns two vehicles. The result? Mobility deserts, isolation, and a growing economic divide for those stuck without wheels.

If the next wave of mobility is going to matter, it won’t be proven in Manhattan or Berlin. It’ll be won (or lost) in the cul-de-sacs and strip malls.

The question is simple:

➡️ Who solves mobility when your neighbor’s driveway is half a mile away?

Suburbia is playing a completely different game.

Most suburban areas were designed around the private car, not around walking, biking, or even efficient public transit. After World War II, North America, Australia, and much of Europe saw a surge in suburban development built on the promise of easy, individualized car ownership.

The results are everywhere — sprawling layouts, cul-de-sacs, big-box stores, endless parking lots.

Suburban mobility today faces three major problems:

1️⃣ First and last-mile deserts

Public transit rarely reaches deep into low-density neighborhoods. Even where rail lines or bus hubs exist, suburban residents often live too far from them to walk comfortably — making the “last mile” a major barrier.

2️⃣ Low-frequency, low-coverage transit

Suburban bus routes aren’t just expensive. They’re inefficient by design.

Low density, long distances, and unpredictable trip patterns mean most suburban transit runs infrequently, if at all. Riders face long wait times, poor coverage, and service that’s no real alternative to driving.

3️⃣ Inaccessibility by design

Suburban streets were built for cars. Wide roads, endless cul-de-sacs, and zoning that separates homes from anything useful make walking or cycling the suburban exception, not the norm. Recent research shows a sharp urban-to-suburban gap in walkability across Europe, with compact city centers scoring far higher thanks to better street connectivity and land use diversity.

Meanwhile, suburban households without reliable car access are trapped.

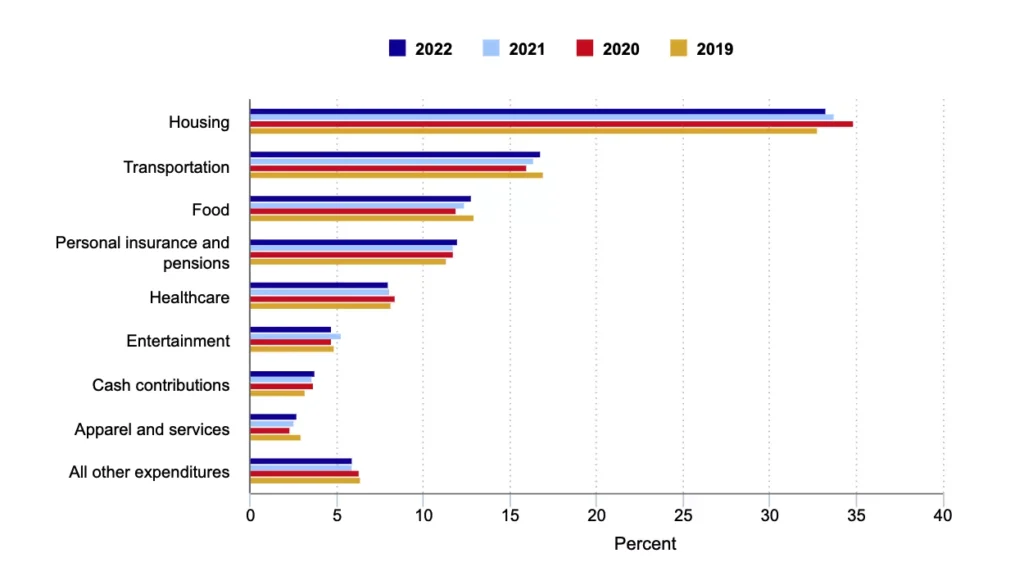

Transportation accounts for about 16–17% of total household spending on average — and that share rises significantly in suburban and rural areas where public transit options are limited.

Suburbs weren’t built for multimodal mobility, but that’s exactly what the future demands.

Solving the suburban mobility gap means redesigning access itself — for e-bikes, scooters, shuttles, and services that meet people where they are, not where planners thought they would drive.

Because the next mobility revolution won’t be won downtown.

It’ll be won — or lost — 15 miles out.

Electric vehicles are no longer just a luxury city purchase.

Suburban drivers — who often face longer daily trips and higher fuel bills — are starting to turn toward EVs worldwide.

But the gap between cities and suburbs is still stubbornly real.

According to the International Energy Agency, EVs accounted for 18% of all global car sales in 2023, up from just 4% in 2020.

China, Europe, and the U.S. are leading the charge and suburban adoption is beginning to show signs of momentum.

The challenge across markets is the same.

Suburban homes are ideal for private, overnight charging, but public charger availability is the weak link.

Without fast, visible, reliable charging infrastructure embedded into everyday suburban life — shopping centers, schools, parks — EV adoption could stall.

Scooters, e-bikes, and light electric vehicles exploded in city centers over the last five years.

But what about the suburbs, where distances are longer, streets are wider, and traditional public transport is scarce?

The good news is — suburbs are starting to see micromobility experiments. And some of them are sticking.

Lime, one of the world’s largest micromobility operators, has launched suburban pilots outside major cities like Chicago, Sydney, and Paris. Instead of serving dense downtown areas, Lime’s e-bikes and e-scooters are being positioned near suburban train stations, shopping malls, and residential neighborhoods.

Early results show that suburban riders tend to take longer trips than urban users — averaging 2–4 miles instead of quick first-mile hops.

Government incentive programs are making e-bikes more attractive for suburban commuters:

These programs recognize a key truth:

For suburban trips between 2–10 miles, e-bikes can be incredible — cheaper, cleaner, and often faster than driving.

If micromobility tackles short suburban trips, what about everything else?

Enter on-demand transit. Flexible shuttle services that don’t follow fixed routes but instead pick up and drop off riders dynamically based on real-time demand.

Think of it like Uber — but shared, scheduled, and usually cheaper.

And in suburbia, where density is low and traditional bus routes flop, on-demand transit might be exactly what fixes the issue.

1️⃣ Via — one of the leaders in on-demand transit — has proven the model at scale:

2️⃣ RideCo, another major player, has partnered with cities across Canada and suburban U.S. markets:

3️⃣ Fflecsi, in Wales, UK:

New suburban mobility models — EVs, e-bikes, on-demand transit — sound great on paper.

But who actually benefits when these solutions hit the ground?

The harsh truth is: mobility innovation often leaves the most vulnerable suburban residents behind.

Research shows cost sensitivity, smartphone access, and payment barriers still block many from using suburban microtransit. A study by the Center for Urban Transportation Research found that high per-ride prices and the need for digital payment apps create real friction for transit-dependent households.

Without affordability and easy access baked in, on-demand systems risk leaving behind the very people they claim to serve.

Traditional car ownership subsidies ($7,500 EV tax credits) still skew heavily toward middle- and upper-income suburban households — not renters or the working poor.

Equity is a design choice.

If suburbs want real, inclusive mobility revolutions, they can’t just deploy shiny new tech.

They have to:

Because if we don’t plan for equity from the start, we’re just paving new deserts with new apps.

It’s easy to pilot a scooter program or run a few on-demand shuttles.

It’s much harder to transform the bones of suburban transportation.

Because the real barriers are deeply baked into the way suburbs were built, funded, and governed.

1️⃣ Infrastructure inertia

Suburban streets are wide, fast, and built for cars — not for shared scooters, e-bikes, or dynamic transit hubs.

Redesigning roadways, adding bike lanes, building charging hubs — all of it is expensive, slow, and politically fraught.

2️⃣ Zoning laws that freeze sprawl

Strict single-family zoning dominates most suburban land.

This pushes homes, jobs, and services far apart — making walking, biking, or even microtransit less viable without major policy overhauls.

3️⃣ NIMBY resistance

Any attempt to densify suburbs, add new transit stops, or reallocate car lanes for micromobility often triggers fierce local backlash:

5️⃣ Fragmented funding and governance

Unlike dense cities with unified transit authorities, suburbs are split across dozens of small municipalities, townships, and school districts.

Coordinating funding for new mobility services becomes a logistical nightmare — and pilot programs often die when grant money dries up.

The barriers are real.

But they’re not permanent.

Change won’t come from tech alone.

It will come from rethinking what suburban streets and neighborhoods are even supposed to serve.

Suburban mobility isn’t doomed to be stuck in gridlock and car dependency forever. Some places are already proving that with the right tools — flexibility, smart investment, and community buy-in — suburban areas can leapfrog into a new mobility future.

Here’s where it’s actually happening:

On-demand microtransit can be the backbone of suburban mobility if done right.

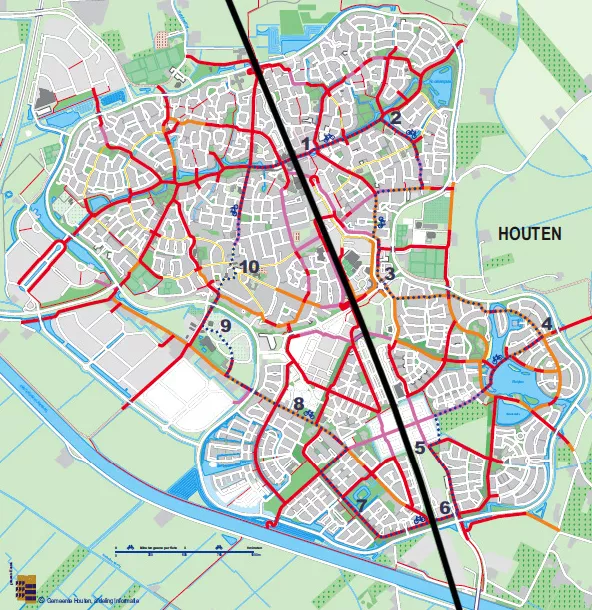

The key? Continuous, safe bike infrastructure — not just around downtowns, but stretching deep into suburban neighborhoods.

Micromobility succeeds in suburbia when it’s designed as a default choice — not an afterthought.

Suburban micromobility needs thoughtful design: infrastructure, regulations, and public trust built together.

Suburbia is the ultimate test for mobility innovation.

The next wave won’t be about copying urban solutions like bike-share docks or dense bus grids.

It will be about building entirely new mobility ecosystems that fit suburban realities. This means long distances, low density, and local independence.

Here’s where the smart bets are moving:

Forget two-mile scooter hops.

Cities like London, Paris, and Utrecht are now planning long-haul, high-speed e-bike corridors reaching 10–30 miles into suburban belts.

Expect suburbs to become the next big battleground for “bike freeways” — connecting homes, job centers, and transit stations without a single car trip.

As EV adoption spreads into suburbs, charging deserts are becoming a bigger risk.

Forward-thinking suburbs are reimagining malls, strip centers, and big-box parking lots as multi-modal EV hubs — with fast chargers, e-bike lockers, car-share lots, and on-demand pickup zones baked into retail spaces.

Shopping centers won’t just sell goods — they’ll sell access.

Suburbs aren’t just where people live. They’re where goods move.

Last-mile delivery fleets, ride-hail drivers, corporate commuter programs — all are shifting toward electrification and shared models.

Expect huge investment in fleet-oriented EV charging, logistics-friendly micromobility, and on-demand corporate shuttles customized for suburban business parks.

Suburbs aren’t a mistake to fix.

They’re the future to rewire.

If cities were Mobility 1.0, suburbia will be Mobility 2.0 — messier, harder, but ultimately more transformational.

The real question isn’t whether mobility can go suburban.

It’s who will figure it out first — and who will still be stuck widening freeways 20 years from now.