From EVs and batteries to autonomous vehicles and urban transport, we cover what actually matters. Delivered to your inbox weekly.

On a crisp morning in Santiago, a sleek red electric bus pulls into a stop along the Alameda. No roaring engine. No choking exhaust. Just the low whirr of a battery-powered machine weaving through the capital’s spine. It’s one of more than 2,700 electric buses now rolling across Chile’s capital — the largest zero-emission fleet in the Americas outside of China.

Meanwhile, in New York City, an electric MTA bus sits idle in a depot, waiting on a charging upgrade. It’s part of a much-hyped transition plan — but only 3% of the city’s 5,800 buses are electric so far.

Across the world, cities are making bold pledges to decarbonize transit. Electric buses are the poster child: clean, quiet, politically popular. But scratch beneath the surface, and a deeper truth appears. the transition is stalling in places that shout the loudest, while quietly accelerating in places few expected.

Buying electric buses is easy — at least politically. They’re the kind of projects that are easy to showcase. Flashy, photogenic, and good for press conferences.. But the real work? That happens behind the scenes, and it’s far less glamorous.

To make an EV fleet run smoothly, cities need more than vehicles. They need upgraded depots, high-voltage grid connections, smart charging software, trained mechanics, and route schedules built around battery ranges, not fuel tanks. This is where most cities stumble — not on ambition, but on execution.

The trap is familiar: buying vehicles without building the ecosystem around them. It mirrors what happened in early EV adoption where governments handed out rebates but forgot about chargers. Transit agencies are now repeating that mistake at scale.

🌆 In Los Angeles, the city’s 2030 target for a fully electric fleet is bumping up against one major issue: the power supply at its own depots.

🏙️ In Toronto, new electric buses arrived before the charging infrastructure was ready, leaving some buses unused. Even in cities with plenty of resources, upgrading depots and coordinating with the power grid is taking longer and costing more than anticipated.

When people talk about EV leadership, they usually point to California, Germany, or Norway. When it comes to electric buses, the real innovation is happening elsewhere. It’s happening in cities that are rethinking how public transit works from the ground up and not just buying clean vehicles.

🇨🇱 Start with Santiago, Chile. Quietly, it’s built the largest electric bus fleet in the Americas outside China — over 2,700 zero-emission vehicles, operating on more than 40% of the city’s trunk lines. And they didn’t get there by building their own vehicles or pumping out subsidies. Instead, Santiago embraced a new model: bus-as-a-service. Operators rent electric fleets from private companies that handle charging and upkeep. It keeps initial costs low, spreads out the risks, and ensures providers stay accountable over the long run.

🇨🇴 Now look at Bogotá. Once known for its diesel-choked TransMilenio corridors, the Colombian capital now boasts over 2,000 electric buses in daily operation. It got ahead of richer cities by teaming up with private companies. They started by electrifying neighborhoods with the worst air pollution, addressing health issues and climate goals at once.

🇨🇳 And then there’s the undisputed giant: Shenzhen, China. The first city in the world to fully electrify its bus fleet — all 16,000 of them. Shenzhen mobilized utilities, trained thousands of workers, and rolled out charging infrastructure across 500+ depots. Centralized planning and industrial strategy powered the transformation. The result? A zero-emission system that moves millions every day, quietly and reliably.

Meanwhile, in cities like New York, London, and Berlin, things are moving slower. They have big goals for electric fleets, but they’re buying buses in bits and pieces, depot upgrades are behind schedule, and they’re still sorting out charging systems. They have enough money, but they’re struggling to get things done.

One of the biggest myths holding cities back from electrifying their bus fleets? That it’s just too expensive.

⚡️ Electric buses do come with higher upfront costs, often two to three times more than diesel models, averaging around $350,000 per vehicle. However, over their lifespan, they can be more cost-effective. Savings on fuel and maintenance can amount to approximately $100,000 per bus. These savings, combined with available federal funding, can offset the initial price difference, making electric buses a financially viable option for school districts in the long run.

⛽️ Diesel buses are fuel-hungry and parts-heavy. Electric buses have fewer moving parts, lower operating costs, and don’t rely on volatile oil markets. A 2023 World Bank study found that electric buses can beat diesel buses on the total cost of ownership (TCO) within five to seven years even without subsidies.

💰 But here’s the problem: transit agencies rarely budget like that. Most operate on tight annual cycles, with capital and operational costs siloed. Buying a diesel bus might look cheaper today, even if it bleeds money over time. And unless cities have access to long-term financing, bond mechanisms, or lease models (like Santiago’s), they’ll keep kicking the can down the road.

You can’t electrify buses without electrifying the infrastructure around them. That’s where many cities are getting stuck.

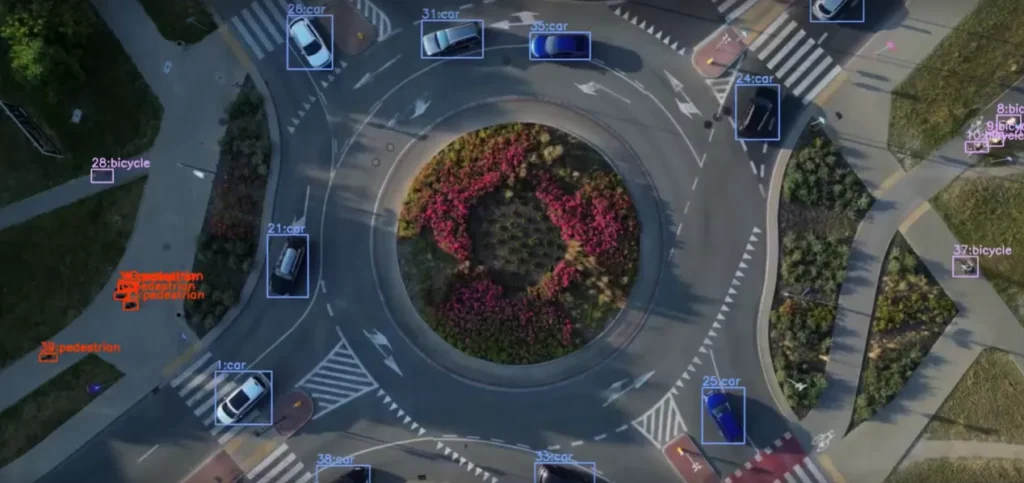

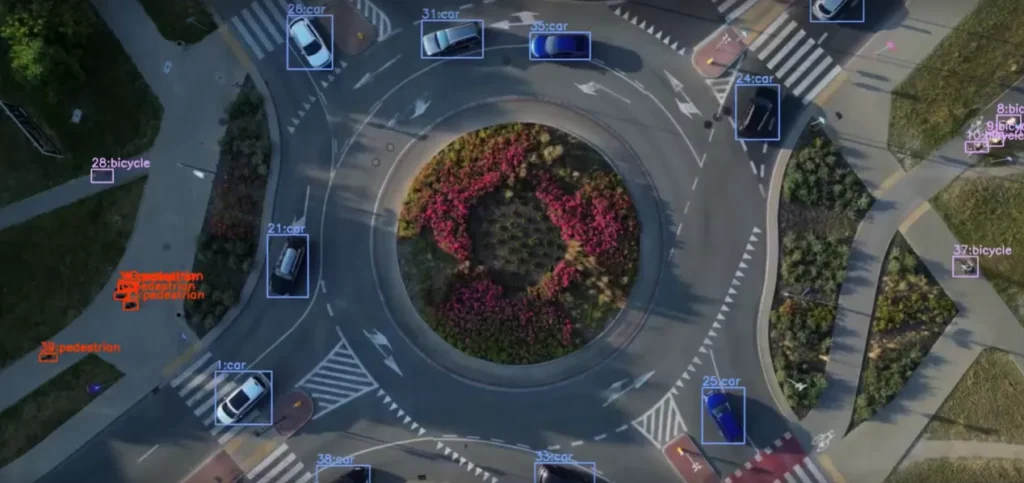

Every electric bus needs a charger, and powering hundreds of buses, especially overnight, demands a lot from the electrical grid. It’s not just about plugging buses in; it means adding transformers, substations, smart charging technology, and coordinating closely with utility companies that typically move slower than transit agencies.

This is the hidden bottleneck.

🏜️ Take Los Angeles, for example. The city wants a fully electric bus fleet by 2030, but it’s already running into delays with utility upgrades and depot charging infrastructure. One early project even saw buses arriving before the chargers were ready. This isn’t only happening in LA; it’s happening in Toronto, New York, and smaller cities across the U.S. too.

Cities need to coordinate closely on grid upgrades, timelines, and energy management. Most transit agencies aren’t prepared for this level of planning, and fewer still include it in their procurement strategies.

But some cities are leading the way:

🇳🇱 Amsterdam partnered with its power utility early, scheduling grid upgrades years ahead.

🇮🇳 In India, projects are experimenting with solar-powered charging and battery storage to ease grid demand.

🇨🇳 Shenzhen succeeded not just because it bought electric buses, but because it built 510 charging depots, integrating smart-grid tech right from the start.

So who’s actually getting this right?

Smart cities are rethinking transit from the ground up and not just buying electric buses. That means better planning, stronger partnerships, and sharper priorities.

Here’s what they’re doing differently:

🔌 Depot-first, not vehicle-first. Electrification starts at the depot. Cities like Shenzhen and Amsterdam began with power upgrades, smart chargers, and energy load planning so when the buses arrived, they could roll out immediately.

🤝 Utilities at the table. Transit agencies that bring utility providers into the planning process from day one avoid years of grid delays later. Santiago did this by structuring long-term operating leases that included charging infrastructure from private partners de-risking the grid load while scaling fast.

💸 Smarter financing models. Cities like Bogotá and Santiago use bus-as-a-service contracts that shift the capital burden off public agencies and tie payments to performance. It’s a model that enables rapid growth without huge upfront costs.

🗺 Prioritize high-impact routes first. Instead of spreading a few buses thin, smart cities concentrate electrification on high-ridership, high-pollution corridors where the air quality and health gains are greatest.

🛠 Invest in people, not just hardware. Shenzhen trained thousands of mechanics and drivers before its fleet went electric. Santiago has prioritized maintenance support as part of vendor contracts.

📈 Redefine success. It’s not about how many electric buses you own. It’s about how many are operating daily, reliably, and serving the routes that matter. Uptime, performance, and rider experience should drive metrics, and not procurement numbers.

The bottom line?

Electrification is a systems problem, and smart cities are treating it like one.

The electric bus revolution is underway, but whether it becomes the norm or just another photo op depends on what cities do next.

Too many rollouts still feel like pilots: a few dozen showcase buses, some ribbon cuttings, and lofty promises. But chargers don’t scale, depots lag behind, and workers go untrained. A year later, the momentum stalls.

The cities that succeed aren’t chasing headlines. They’re building boring, coordinated systems that work. No drama. Just uptime.

That’s what this moment needs: less hype, more follow-through. Because if we get it right, EV buses won’t just cut emissions; they’ll redefine how cities move.

What would it take to make electrified public transport the default, not the exception — especially in the cities that need it most?