From EVs and batteries to autonomous vehicles and urban transport, we cover what actually matters. Delivered to your inbox weekly.

Nearly half of all U.S. vehicle trips cover less than three miles. Most of them happen on quiet streets, inside business parks, college campuses, or downtown corridors where speed limits top out at 35 mph. Yet these short routes are still dominated by gas vans, pickups, and golf-cart conversions that were never designed for daily commercial use.

That short-trip blind spot is where Waev has planted its flag.

From its base in Anaheim, California, the company builds a full ecosystem of low-speed and utility EVs, engineered for every task that doesn’t need a freeway.

Where most automakers chase range, horsepower, and charging voltage, Waev is going the other way – trimming excess, simplifying hardware, and optimizing for the miles that make up the majority of real-world driving.

When Polaris Industries bought GEM in 2011 and Taylor-Dunn in 2016, their goal was to add electric capability to a powersports empire built on ATVs and snowmobiles.

But within a few years, it became clear that the slow-moving, low-speed segment didn’t fit the company’s DNA. GEMs weren’t adrenaline machines, but quiet workhorses shuttling staff and supplies across campuses, airports, and neighborhoods.

By 2021, five senior Polaris executives – Keith Simon, Paul Vitrano, Cosmin Batrin, Jon Conlon, and Luke Mulvaney – saw an opening. They led a management buyout of the GEM and Taylor-Dunn divisions, forming Waev Inc. on December 31, 2021. The deal freed two veteran brands from the noise of high-performance powersports and put them under leadership focused entirely on electric utility and fleet applications.

Independence immediately changed the roadmap. Within a year, Waev rolled out lithium-ion versions of Taylor-Dunn’s Bigfoot and the Tiger ground-support tractor, followed by new GEM models with longer-range LiFePO₄ packs.

By 2023, the company had a credit facility from JPMorgan Chase to scale production, and by 2024 its lineup covered everything from campus shuttles to airport tugs. The 2025 launch of the Fusion fleet cart line and a Best Buy online retail partnership signaled how far the brand had evolved… From a niche leftover from Polaris to a full-scale EV OEM with mainstream reach!

Today Waev operates through more than 400 dealers and manages a portfolio of three core brand, GEM for on-road mobility, Taylor-Dunn for industrial logistics, and Tiger for aviation and heavy-tow duties, with Fusion rounding out the lighter commercial segment.

Waev’s advantage is in the coordinated lineup that covers nearly every job under 35 mph.

The original LSV now runs up to 125 miles per charge and comes with a 7-year LiFePO₄ battery warranty. GEMs handle everything from campus security to resort shuttles and city circulators like Anaheim’s FRAN.

New variants add HVAC, wheelchair access, and even an ambulance option. All meet full FMVSS 500 safety standards — seatbelts, glass windshield, airbags optional — so they replace vans and pickups for most short routes at a fraction of the cost.

A 70-year warehouse icon now running lithium. The Bigfoot Li-Ion carries 3,000 lb and tows 10,000 lb for about 60 miles per charge. It’s still the same steel frame crews know, just without oil changes or downtime.

Built for ground support. Up to 60,000 lb towing, fast-charge-ready, and fitted with a patent-pending anti-rollover system. Available in gas or electric, with a Repower kit that converts old tractors to Li-ion in a day — a practical bridge for airports chasing zero-emission targets.

Launching late 2025, Fusion brings lithium-ion power and factory safety gear to the golf-cart world. Configurable for 2–8 passengers or cargo, it ships with a 5-year battery warranty and app-based diagnostics.

Together, these four brands give Waev a complete “local-fleet stack” – street, campus, factory, and airport – proving that right-sized EVs can do real work without ever touching the highway

Waev builds around what fleets actually trust. Every new model runs on LiFePO₄, a safer, longer-cycle lithium-ion chemistry known for thermal stability and zero maintenance.

Each pack is paired with Waev’s in-house battery management system and thermal insulation that keeps charge and performance consistent from –20 °F to 140 °F.

It’s a design for uptime – no watering, no corrosion, no winter sluggishness.

Charging stays simple. All vehicles accept a standard 120 V wall plug, step up to 240 V for faster turnaround, and most use a J1772 connector. The heavy-duty Tiger EV adds DC fast-charge support for quick airport or industrial shifts.

Waev’s integration approach leans on proven partners:

The result is a platform built on reliability, not experimentation. GEM’s 7-year battery warranty and Fusion’s 5-year coverage are practically unheard of in commercial EVs.

Waev’s vehicles are already clocking hours in universities, city fleets, resorts, airports, and industrial campuses – the places where short trips dominate and downtime costs real money.

Universities and campuses were the earliest adopters. Facilities teams use GEMs for maintenance, security, mail runs, and student transport. Across a typical fleet of 1,000 combustion vehicles, replacing half with GEMs can save about $6 million over seven years in fuel and upkeep. They’re quiet, zero-emission, and simple to service – three reasons why campus fleet managers keep expanding orders.

In municipal operations, GEMs double as parking enforcement and park department shuttles. Anaheim’s FRAN electric shuttle network runs GEM-based LSVs through downtown, replacing millions of car trips each year and proving that “low-speed” can still move a city.

Airports are where the heavy hitters live. The Tiger EV tow tractor now works baggage and cargo lines, cutting fuel and maintenance costs by roughly 80 percent compared with diesel tugs. For older fleets, the Tiger Repower kit lets ground handlers electrify existing tractors instead of buying new, an instant sustainability win that airport CFOs can justify.

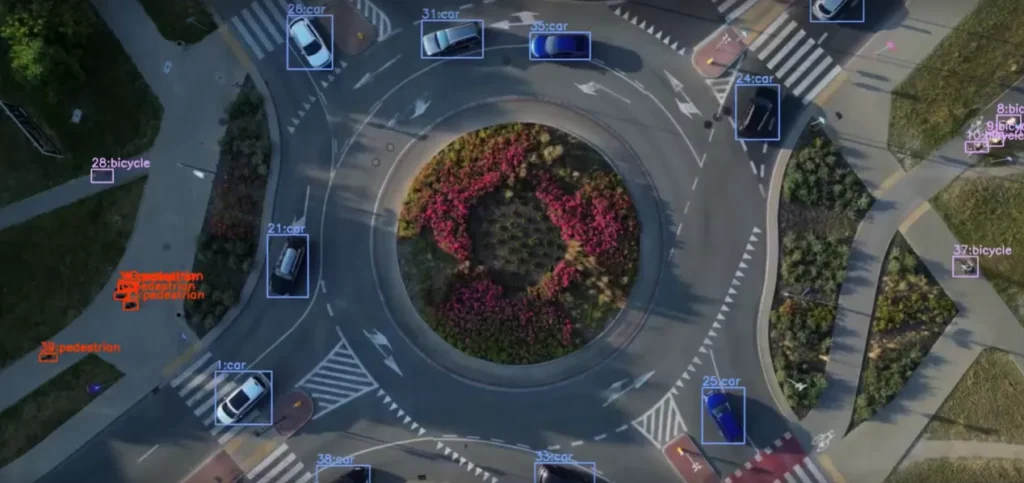

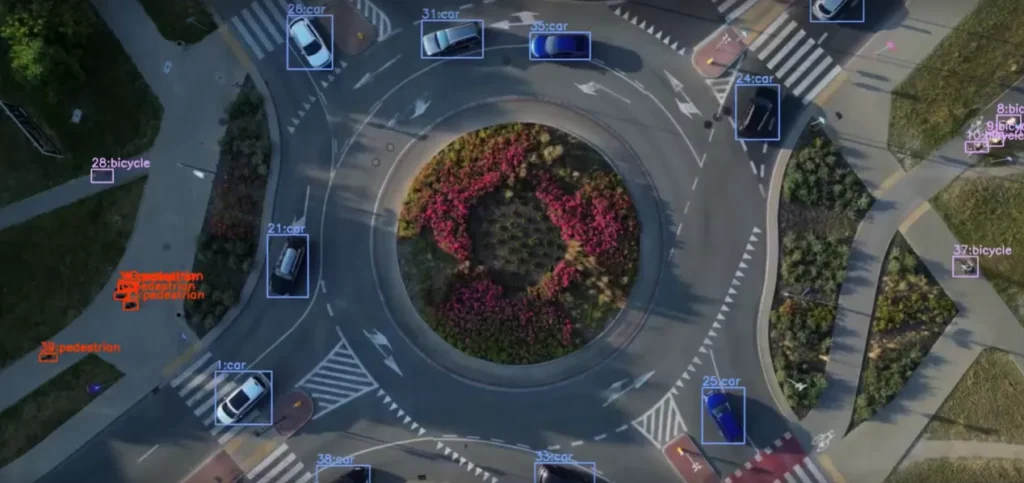

Even autonomous transport pilots are using Waev platforms. Jacksonville’s transit authority deployed a GEM shuttle outfitted by Perrone Robotics, part of its ongoing AV testing program. The vehicle’s low speed, compact footprint, and safety compliance made it a natural fit for public-road trials.

And the numbers are consistent across all use cases – 3,000+ charge cycles, full-day range, and near-zero unplanned downtime. For fleet managers used to constant oil changes and brake jobs, Waev’s simplicity is its main selling point.

As one university fleet director put it after switching to GEMs: “They just work. Plug them in at night, and they’re ready every morning. That’s all the team really wants.”

Waev’s distribution strategy looks more like a tech platform than a traditional automaker. Instead of a single pipeline, it runs on several parallel tracks, each built for a different type of buyer.

The company now operates through 400+ dealers across North America, mixing industrial equipment distributors, golf-cart and powersports dealers, and airport GSE specialists. That hybrid network means a university facilities team, a factory manager, and an airline ground-ops director can all buy from local partners trained on Waev products and parts.

For public-sector fleets, Waev made procurement frictionless. It holds a Sourcewell contract (#091024-WVE), recognized by more than 50,000 government agencies in the U.S., and a matching Canoe agreement in Canada. Cities, schools, and airports can order vehicles directly under those pre-approved terms without running their own bids.

Financing follows the same logic. Through a partnership with DLL (Rabobank Group), dealers get floorplan credit to stock inventory, while customers gain access to leasing and loan programs that spread costs over fleet lifecycles. That’s crucial for municipal and institutional buyers budgeting by fiscal year rather than cap-ex cycles.

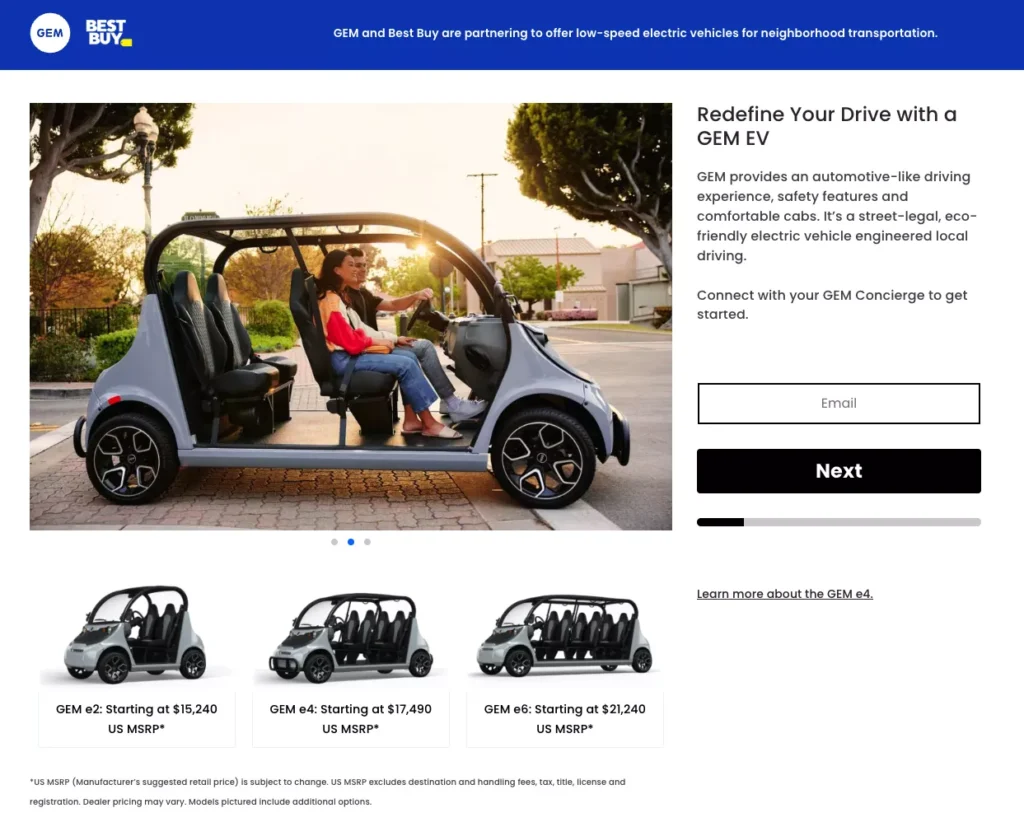

Then there’s the retail wildcard. In 2025, Waev put GEM on BestBuy.com, making it the first street-legal EV sold through a mainstream electronics retailer. Buyers can spec a vehicle online, check out with a concierge, and have delivery coordinated through local dealers—a simple bridge between e-commerce and fleet sales.

On top of that sit Waev’s integration partners – Driverge for the wheelchair-accessible WAV, Par-Kan for airport service upfits, and Perrone Robotics for autonomous GEM pilots.

Put together, Waev’s go-to-market looks omnichannel by design. Government contracts, B2B leasing, and consumer e-commerce – all feeding into the same production stack.

Electrification usually comes with sticker shock. Waev flips that equation by focusing on the use cases where the math already works.

A GEM that replaces a pickup or small van costs roughly $0.03 per mile to operate, including electricity and maintenance. Over seven years, that difference translates to tens of thousands in savings per vehicle, before counting tax incentives or parking benefits.

At the heavy end, the Tiger EV tow tractor cuts operating costs by up to 80% versus a diesel tug. Each unit avoids around 3.25 metric tons of CO₂ emissions per year, all while delivering the same towing performance.

Across campuses, factories, and airports, the pattern holds: short routes, low speeds, and repeat duty cycles make right-sized EVs far more cost-effective than large battery vehicles. They charge from standard outlets, require no infrastructure overhaul, and fit directly into existing workflows.

Even in a category built for stability, Waev faces a few pressure points worth watching. None of these are existential risks, but they will demonstrate Waev’s abilities to overcome the odds, as they’ve been doing since their start in December 2021.

Battery sourcing. Most of its lithium cells come from Asian suppliers like Marxon, and while LiFePO₄ chemistry is proven, any disruption in that supply chain could slow production or raise costs. Waev integrates packs in-house but doesn’t manufacture cells, so it’s exposed to the same bottlenecks that hit larger OEMs.

Policy uncertainty. Low-speed vehicles currently sit in a gray zone of U.S. incentives. Waev has pushed for IRA tax-credit eligibility, arguing that short-trip EVs displace as much fuel per dollar as long-range models. If regulators don’t budge, it limits adoption in municipal and fleet programs tied to federal funding.

Dealer reach. The company’s 400-dealer network is deep across the U.S. but thinner overseas. Expansion into Europe or Asia would require new compliance work, service infrastructure, and local assembly, none of which come cheap.

Financing sensitivity. Fleet sales rely on leasing programs through DLL. Persistently high interest rates could dampen volume or push customers toward cheaper, non-compliant carts.

Execution on new channels. The Fusion launch and Best Buy partnership are ambitious plays outside Waev’s core industrial base. Both will test whether Waev can manage consumer expectations and retail logistics without diluting the B2B focus.

While most of the EV spotlight goes to long-range cars and highway chargers, the real transformation is happening closer to home. Cities are tightening downtown access for combustion vehicles, campuses are going fully electric, and airports are phasing out diesel GSE.

All of that expands the low-speed, short-trip territory where Waev already leads.

If the company keeps converting Sourcewell bids, scales Fusion fleet sales, and proves that Best Buy’s retail experiment can bring new customers into the fold, Waev could quietly become the default supplier for local-range EV fleets—from city crews to resort shuttles.

The key signals we’ll watch – adoption of Tiger Repower conversions at airports, Fusion deliveries through dealer networks, and whether Waev starts pushing into micro-delivery or last-mile logistics.

While the rest of the industry obsesses over 400-mile batteries and 350-kW chargers, Waev is electrifying the miles we actually drive the most.