From EVs and batteries to autonomous vehicles and urban transport, we cover what actually matters. Delivered to your inbox weekly.

For decades, cities have treated parking as the cure for congestion. More garages, bigger lots, more curbside stalls. The assumption was that traffic would ease, businesses would thrive, and drivers would stop circling the block.

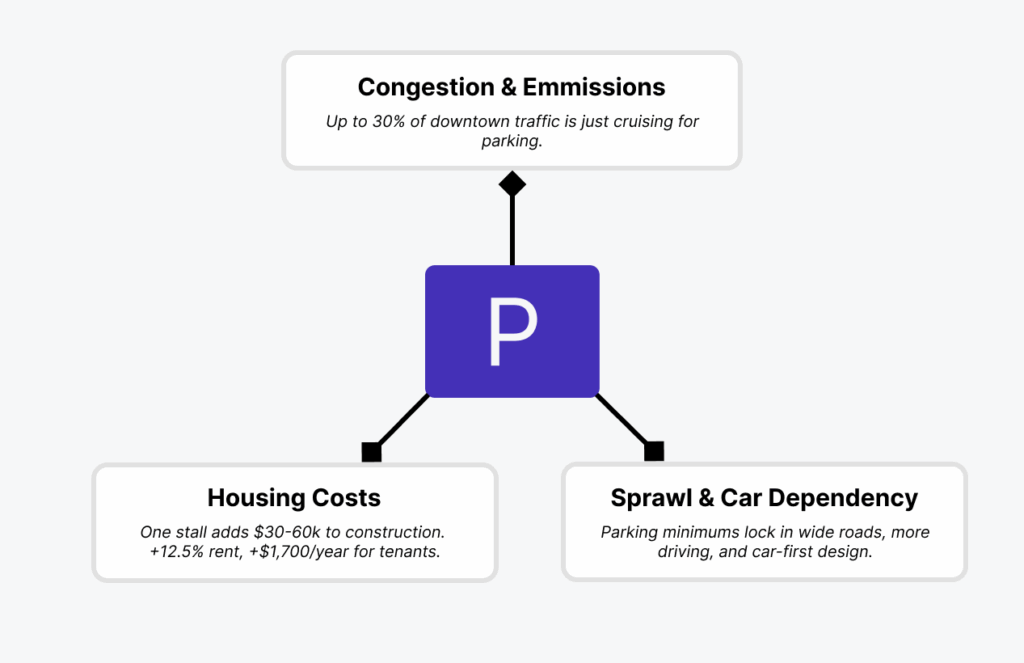

The outcome has been the opposite. Abundant parking encourages more driving, locks households into car ownership, spreads development farther apart, and raises housing costs. It also leaves streets clogged with emissions from trips that might never have happened if other options were available.

This is the parking paradox. The very thing meant to keep cities moving has made them harder to live in. And the policies behind it continue to shape urban life today.

In this deep dive, we’ll look at:

It’s time to ask what all that “free” space is really costing us.

For decades, parking policy has rested on three assumptions:

The evidence shows otherwise.

The belief that congestion can be solved by adding spaces has been disproven repeatedly.

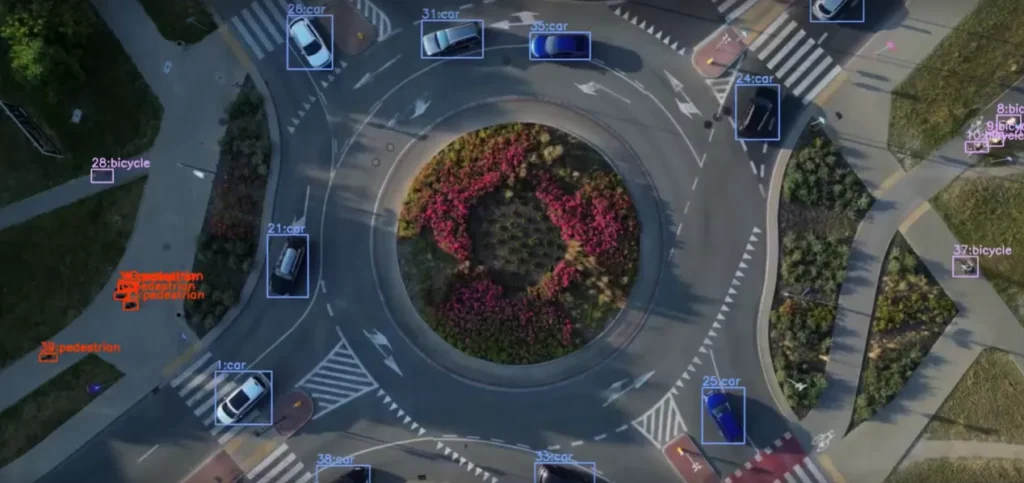

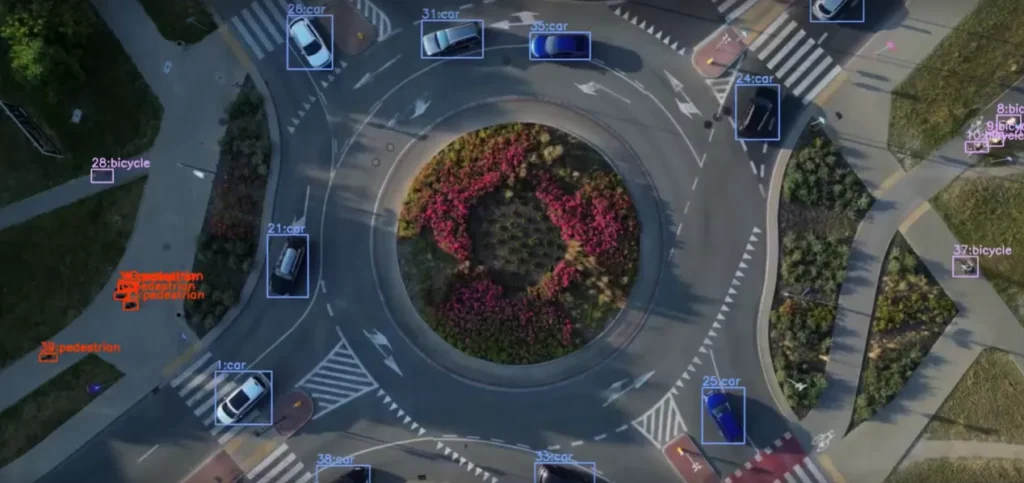

Donald Shoup’s research found that cruising for parking makes up as much as 30 percent of traffic in downtowns, adding millions of miles and significant emissions each year. In Los Angeles business districts, drivers spent an average of 3 to 14 minutes searching for a space. What looks like a short errand becomes a source of gridlock.

San Francisco’s SFpark program offered a different solution. Instead of building new garages, the city installed sensors and adjusted curbside prices block by block. The target was to keep spaces between 60 and 80 percent full.

This resulted in less cruising, fewer double-parked vehicles, and more predictable availability. In many areas, average hourly rates even fell because demand was lower than assumed.

The lesson learned here is – building more parking doesn’t reduce congestion. It induces demand, encouraging trips that would not have happened otherwise.

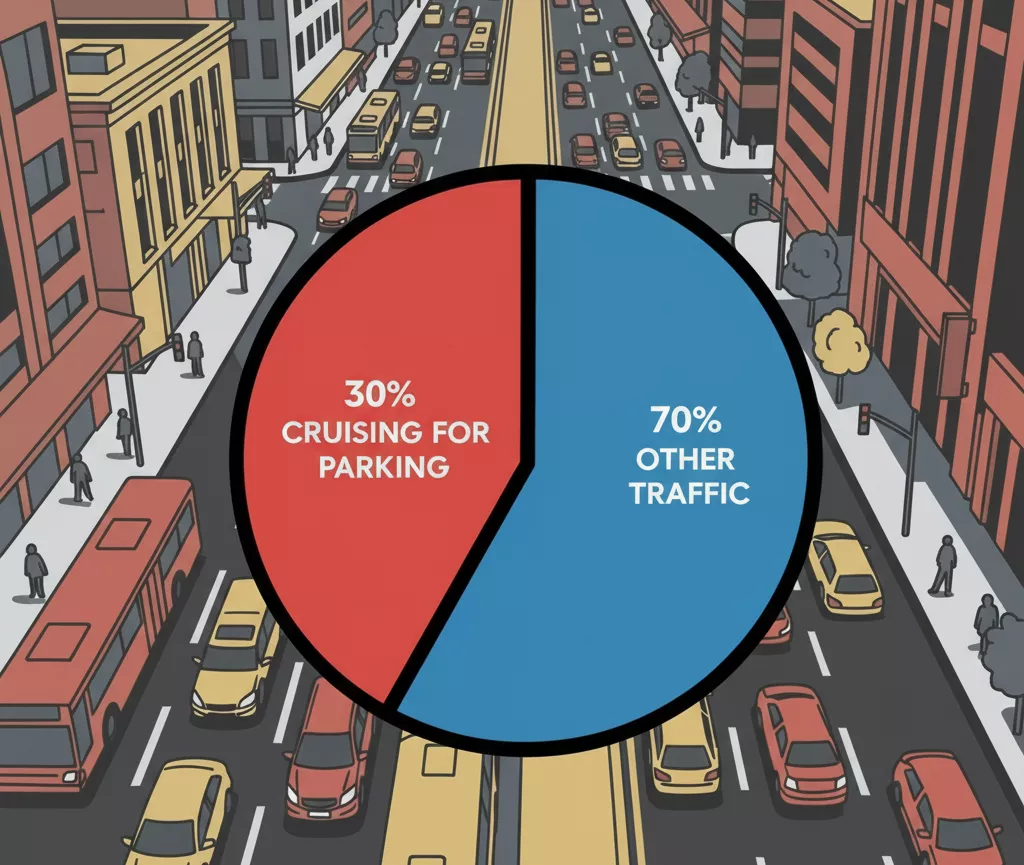

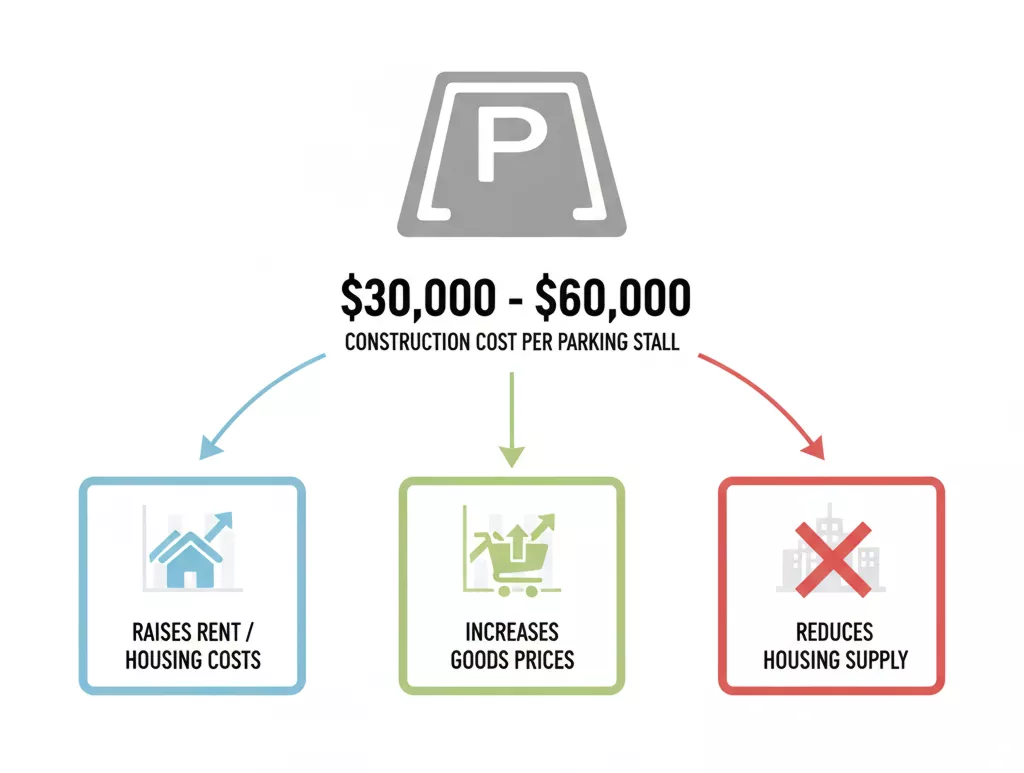

Drivers rarely consider the cost of parking, but each stall carries a steep price. Structured parking typically costs $30,000 to $60,000 per space to build, depending on land and design. Those costs are passed on through higher rents, more expensive goods, and development compromises.

King County’s “Right Size Parking” study showed that requiring a single stall per apartment increases monthly leasing costs by about 12.5 percent. For households without cars, that’s wasted money. A UCLA study found that bundled parking adds $1,700 per year to housing costs, effectively making renters subsidize car owners.

These hidden costs limit affordability, reduce housing supply, and make it harder for lower-income households to live near jobs or transit. Far from being “free,” parking is one of the most expensive line items in city building.

Local businesses often argue that fewer spaces mean fewer customers, but data from multiple cities proves the opposite.

In Toronto, retail sales on Bloor Street rose 4.45 percent after on-street parking was converted into bike lanes. In New York City, corridors that reallocated parking to protected cycling lanes reported higher sales and more frequent visits. Amsterdam has steadily reduced its parking supply for decades, reclaiming space for cycling and pedestrians, while maintaining some of the strongest local retail performance in Europe.

People, not cars, drive commerce. Customers arriving by foot, bike, or transit tend to visit more often and spend more locally than drivers passing through. Streets with wider sidewalks, safer crossings, and cycling infrastructure invite activity that parking lots cannot.

In practice, reducing excess parking often strengthens business districts rather than weakening them.

Endless lots and underpriced curb space may look like convenience, but they create cities that are less efficient, less affordable, and harder to live in.

Oversupply doesn’t ease traffic, it increases it. When curb space is cheap or free, cars spend more time circling for the best spot, adding miles to every trip. Studies estimate that up to 30 percent of downtown traffic is just cruising for parking. San Francisco’s SFpark program showed that demand-based pricing can cut this waste entirely.

Cheap, abundant parking also lowers the cost of every car trip. The result is higher vehicle miles traveled (VMT), more emissions, and streets choked with trips that might never have happened if alternatives were competitive.

Every parking stall carries a steep construction cost (often $30,000 to $60,000) and those costs flow directly into rents and leases.

King County’s “Right Size Parking” study found that requiring one stall per apartment increases rents by 12.5 percent. A UCLA study showed bundled parking adds about $1,700 a year to housing costs, even for tenants without cars. The effect is that low-car households subsidize empty stalls while overall housing supply shrinks.

Parking mandates make homes more expensive and less plentiful.

Parking rules shape more than buildings. They shape neighborhoods. Parking minimums in zoning codes across North America and elsewhere have produced wide roads, strip malls, and subdivisions where every errand requires a car.

This design creates a cycle – more parking encourages more driving, which fuels calls for even more parking. The pattern locks cities into car-first planning that lasts for decades.

As a good example, just check how Tempe, AZ solved this issue. A new community has been designed and built, putting human connections at the forefront. Zero cars, but a ton of micromobility options to get around. And so far, it seems to be working perfectly.

If parking created today’s problems, smarter rules are showing the way out. Around the world, cities have tested reforms that reshape how streets, housing, and mobility work.

In 2011, San Francisco launched SFpark, the first large-scale program to treat curbside parking as a managed resource instead of a free giveaway. Sensors monitored occupancy in real time, and prices were adjusted block by block to keep spaces 60 to 80 percent full.

Cruising times dropped, double-parking declined, and availability became more predictable. Revenue stabilized because prices reflected demand. Importantly, average hourly rates actually went down on many blocks where usage was weaker.

SFpark showed that better pricing can manage traffic and parking demand more effectively than building new supply.

For decades, zoning codes across California forced developers to provide a fixed number of stalls for each unit, regardless of whether residents wanted or needed them. That changed in 2022 when the state passed AB 2097, eliminating parking minimums within a half-mile of major transit stops.

The impact has been significant. Developers now choose how much parking to provide. Early projects in Los Angeles and San Diego report higher housing yields, lower construction costs, and faster approvals. Some landlords are unbundling parking from rent, allowing tenants to avoid paying for spaces they do not use.

Amsterdam has pursued one of the most ambitious parking reduction strategies in the world. Since 2019, the city has phased out about 1,500 on-street permits each year, with the aim of reclaiming thousands of spaces by the end of the decade.

The reclaimed curb space has been redesigned for protected bike lanes, wider sidewalks, street trees, and outdoor commerce. So far, the results include safer streets, stronger local retail activity, and a steady increase in cycling and public transport use.

Amsterdam’s gradual approach shows that reducing parking is politically viable when it is paired with visible improvements and alternatives.

Tokyo took a different path, addressing oversupply at the source. Since the 1960s, buyers must present a proof-of-parking certificate before registering a car. The rule requires an off-street stall within two kilometers of the home address.

This system has kept on-street parking to a minimum, discouraged speculative ownership, and reserved public space for transit, deliveries, and cycling. Despite being one of the largest metro areas in the world, Tokyo’s streets remain remarkably clear of stored vehicles.

These examples show that parking reform is not theoretical. San Francisco managed demand with pricing, California removed costly mandates, Amsterdam reclaimed streets through gradual removal, and Tokyo enforced supply limits through regulation. Each city applied a different lever, but all reduced congestion, cut emissions, and freed up urban land for better use.

If oversupply of parking helped create congestion, emissions, and affordability problems, then reforming how cities handle it can be part of the solution. The cities making progress tend to follow the same set of steps, and those steps also create opportunities for mobility startups.

Curb space is some of the most valuable land in a city, yet it is often free or underpriced. Dynamic pricing changes that equation.

Mandatory minimums require developers to build stalls even when they are not needed. That raises costs, reduces flexibility, and crowds out housing.

Reclaiming parking creates space that directly improves city life.

Japan addressed oversupply decades ago by requiring car buyers to prove they had an off-street stall before registering the vehicle.

Parking reform works best as a set of coordinated tools. Pricing curbs, cutting minimums, reclaiming space, and requiring proof of supply each address a different part of the problem.

Together they create cities that are more livable, more sustainable, and more open to innovation.

Parking is not only about where cars are stored.

Parking shapes housing costs, climate emissions, traffic levels, and the strength of local economies. Each new garage or surface lot deepens car dependency, while each curb that is reformed creates opportunities for housing, transit, micromobility, and commerce.

This makes parking reform a climate strategy as much as an urban planning tool.

The lessons from San Francisco, Los Angeles, Amsterdam, and Tokyo point to the same conclusion – price curb space, end minimums, reclaim land for people, and set clear rules that keep streets open for movement rather than storage.

Cities can continue investing in more lots and wider roads, or they can reclaim asphalt for people, new services, and cleaner forms of mobility. Those that act decisively will be healthier, more affordable, and more competitive. And those that delay will inherit growing seas of underused parking and the emissions that come with them.